The Antarctic Peninsula under a 1.5°C global warming scenario

After the accidental disappearing of my blog (and, ironically, the temporary disappearance of that link), today is a minor “relaunch” with a new banner and a new format of shorter, more frequent posts.

——//——

A tale of Antarctica

When I was a child, I found a squirrel tail in a dry, dusty garden. I remember holding my breath at its papery fragility, the gentle curve on my palm. Most of all, I remember the delicate skeleton – the interlocking ridges of the bones, tapering to a fine point.

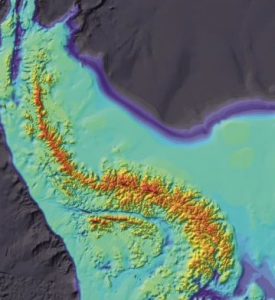

Skeleton of a grey squirrel tail. Bedrock beneath the Antarctic Peninsula.

I am reminded of that bony fragility and gentle curve when I look at maps of the Antarctic Peninsula – especially maps of the bedrock beneath, revealing the spine of mountains, the interlocking ridges that taper to a fine point.

Today we published a briefing paper on the Antarctic Peninsula under a 1.5°C global warming scenario, the most ambitious target for limiting warming under the Paris Agreement. The Peninsula is a unique part of the continent, reaching further north than the rest – towards South America – and consequently more vulnerable to warming. The rest of the vast ice sheet will feel global warming more slowly, because it lies further south and is fortified by the vastness of the white landscape that reflects more of the sun’s warmth away. Great circles of wind and ocean currents around the continent help to protect it further, forming a buffer against the warming of human endeavours.

The Peninsula has warmed by over 2.5°C, around two and a half times faster than the global average. Warmer air: more melting. In 1995, a floating ice shelf fringing the eastern tip, Larsen A, disintegrated into the dark ocean. In 2002, its larger southern neighbour Larsen B followed. These wholescale shelf collapses are thought to be caused by surface melting, largely caused by us.

Ice shelves are important because they act as a brake on sea level rise: like dams in rivers, they can slow the flow of ice into the sea. Once collapsed, the upstream glaciers flow more quickly and the seas rise. This is compounded by warming of the water that melts the ice from beneath. Fortunately, the region’s small area and mountain ranges mean it is not contributing a large amount to global sea level rise (around 0.1 mm per year, or around three per cent of the total).

What future for the Peninsula under climate change? Like many things, it’s not a simple story of bad or good news. A large chunk of the next ice shelf down, Larsen C, broke off in 2017. But, huge as it was – twice the size of Luxembourg – it was only a chunk, around 12% of the shelf, rather than a full collapse. Icebergs breaking away, travelling across the oceans before they melt, are not necessarily bad news or signs of climate change, because ice sheets shed icebergs like snakes shed their skin. What matters is whether they become more frequent, more widespread, lead to more ice flow. Current predictions are that the Peninsula’s remaining ice shelves may be stable under 1.5°C of warming, perhaps even more. Even if this is too optimistic, the potential sea level rise it contains is not as large as other regions of concern.

But this northern finger of ice is a portent of how further warming could affect the rest of the continent, the white canary flying out from the Southern Ocean. More melting from underneath in other parts of Antarctica, and more ice shelves collapsing, means more sea level rise, and in those places the amount of ice is effectively without limit on timescales of hundreds to thousands of years. We don’t yet know how the future of the ice sheet might be foretold by this tale of early vulnerability.

Our briefing also covers other aspects of the Peninsula. New land areas have been exposed (currently around 3% of the Peninsula), and these areas are predicted to expand further even under 1.5°C of warming. This might encourage non-native species, which could threaten the native species already made vulnerable by over-fishing and exploitation. The briefing is intended for a general audience, with a nice infographic (linked below), so do take a look.

——//——

Round up

I am excited to be analysing the first Greenland and Antarctic ice sheet projections coming in for the international project ISMIP6, which will form the core of the sea level rise projections in the next major report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (a slow process – it will be published in 2021). Plotting new data is always fun, but I also feel the responsibility of how we can best interpret and assess the numbers to give the most reliable information to policymakers that we can.

Talking of interpreting the numbers, I was interviewed with my oncologist by the BBC radio program More or Less, about how it feels to deal with the numbers of cancer. It’s quite upbeat, but does talk about how to deal with – and support someone through – some of the more difficult aspects of a diagnosis and treatment.

Further to pessimistic scenarios, I am reading The Uninhabitable Earth: A Story of the Future by David Wallace-Wells. As you would expect from the title, the story it tells is one of the worst case, or in my view worse-than-worst-case, scenario – in terms of our climate policies, the earth’s response to them, and our own vulnerabilities. But it is mostly quite clear about that, and well-referenced, so I’m finding it a useful summary of the bounds of the possible.

I am disoriented by the new feeling in the air about climate change. Greta Thunberg and the school strikes, the Extinction Rebellion protests, the UK’s commitment to reduce carbon emissions to net zero by 2050 – all are making climate change a normal topic of conversation, which is new to me. More people want to talk about the climate, and more of the media want interviews: the weather, the forests, the ice, the politics. It is wonderful, and sometimes a little overwhelming.