How to love uncertainty in climate science

This is the script of my TEDxCERN talk, a 12-13 minute talk I did from memory. When the video is put online in a week or so, you’ll be able to follow along and see where I fluffed it improvised. A shorter version appeared on Vice News under the headline “There Is Some Uncertainty in Climate Science — And That’s a Good Thing”.

I used to be a particle physicist. Sadly, I left before it became cool to be a particle physicist.

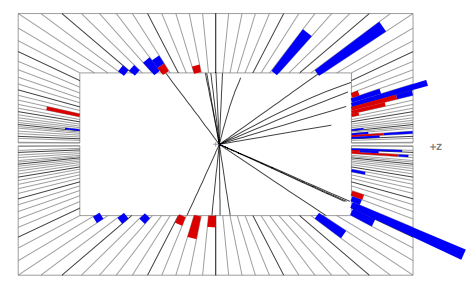

Here’s one of the collisions I observed for my PhD at Fermilab:

And in that previous life, the stringent criteria for being “certain” about a new discovery, like the Higgs boson that made headlines at CERN, is the 5 sigma confidence level.

Here’s the famous “bell curve”, with the sigma levels shown along the bottom:

You can see that 5 sigma is way out in the tails, with a very, very low probability of occurring by chance. It means we think there is only a one in 3.5 million chance that the signal could have been seen if there no Higgs.

Now that I’m a climate scientist, I dream of such certainty! We’re studying an enormously complex planet. I’m going to talk about some of the reasons there’s uncertainty in climate science, some of the problems that’s causing between science and society, and what I think we can do about it.

I’ll start with some things we’re certain about. The earth’s energy budget is out of balance: there’s more energy going in than coming out, so the planet is storing it up. That’s not unusual in itself, only that we are helping tip the scales. The extra energy means the atmosphere and the surface of the ocean have warmed, making the hottest days warmer and more frequent, and the coldest days less frequent.

As the oceans heat up they expand, and ice on land – in glaciers, and the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets – has also been melting into the oceans, and breaking off in ice bergs, faster than it has been replaced by new snow. So global average sea level has risen. We’re confident our activities have been the dominant cause of warming since the middle of the last century.

How about the future? We predict more of the same. We’re confident the world will get warmer, shifting the hottest and coldest days further, and that rainfall will become heavier in some places, such as the wet tropical regions. Global average sea level will continue rising, making the extreme highs in sea level higher and more frequent.

But it’s not only climate scientists that are certain. Not everyone knows this, but more and more climate sceptics agree with us too. Yes, there are people who don’t believe CO2 is a greenhouse gas, and likely never will. But in my experience many sceptics in the blogosphere, media and politics absolutely agree we are having an effect on climate. They question only the details, such as how fast that warming will be, or how we should reduce the risks.

How do we know what we’re talking about? The big picture predictions come from our observations of the planet and our fundamental physical understanding, some of which is 200 years old. But the details – exactly how fast temperatures and sea levels will rise, and which parts of the world will experience heavier rainfall – must come from computer models.

Here’s a map of the world in a climate model:

The model’s about 15 years old, but it’s still used. You can see the world has been simplified: it looks blocky, almost like a very early digital camera.

We need to use computer models because we don’t have a miniature earth to play with. It’s not only climate science with this difficulty. If you want to study, say, the evolution of galaxies, it’s a bit easier to write computer code than to create a hundred million stars… At the heart of climate models are basic laws of physics, like Newton’s laws of motion, and over time we’ve added more and more physics, chemistry, biology and geology.

But a model can never be perfect: it is by definition a simplified representation of reality. There’s a great saying by this statistician George Box, who sadly died last year: “All models are wrong, but some are useful”. I think this is so important I named my blog after it.

Not only are all models simplified, but their predictions partly depend on the numbers you plug in. And we can’t always know what those numbers should be: say, if they’re hard to measure in the real world. So there’s uncertainty because of the simplifications and unknown inputs of our computer models.

A second reason is that the very definition of climate has uncertainty at its heart. People often think of weather and climate as the same thing, but they’re not. Weather is the state of the atmosphere: the temperatures, rainfall and pressures we can measure with instruments. Climate is different. We can think of climate as “the probability of different types of weather occurring”.

The fact that climate is a statement of probability means two important things. First, that climate is inherently uncertain. A probability is a statement of uncertainty. “We predict the weather will mostly be X, sometimes Y and occasionally Z”.

Second, it means that climate is a long-term thing. That’s because to estimate a probability you need a lot of data. If you were flipping a coin to see if it’s fair, 50:50 heads or tails, you’d have to do it a lot of times before you could be sure. In the same way we need around 30 years or more of weather records to get just one data point of climate. So that fact that climate is a probability means that it’s uncertain and that we need a lot of data to test our models.

My research focuses on both sources of uncertainty I’ve mentioned: the limitations of computer models, and testing their predictions.

Uncertainty doesn’t mean we don’t know anything. In fact I’d argue that uncertainty is the engine of science, because it drives our search to understand the universe. But misunderstanding and misrepresentation of uncertainty is damaging the relationship between climate science, the media and society, because climate science is both complex and highly politicised.

The first problem uncertainty brings is the extra difficulty for the expert in explaining their results, and the non-expert in understanding them. For example, over the past 17 years or so there has been a slowdown, even a pause, in the rate of warming of the atmosphere. We’re confident the climate is still changing, because the ocean is still warming, the land losing ice, sea level rising, and we predict the atmosphere will start to warm again after this temporary blip.

We think there are several contributing factors to this pause, including a change in the movement of heat around the planet, a dip in the brightness of the sun, reflection of the sun by pollution and volcanic eruptions. But because we need to use computer models to understand it, and because 17 years is not that long when it comes to climate, we don’t know the exact contributions of each. Clearly this is not simple, sound bite science.

The second problem is that scientists in any area of cutting edge research will disagree with each other. If the media or public don’t expect that it can cause confusion, and, worse still, because climate science is politicised, these disagreements are often sold as proof of “unreliable science”, an argument to ignore scientists until it’s all “sorted out”.

For example, some scientists predict global average sea level rise under the highest greenhouse gas emissions scenario will likely be 20 to 30 inches by the end of the century. Others predict it will very likely be 3 to 5 feet, or possibly over 6 feet. That’s a big difference! The reason is that the two groups look at the problem in quite different ways – the first use methods based in physics, the second statistics. That’s an interesting story to tell, because we don’t yet know the best approach.

We might like to think of science as a neat, orderly book of facts, but really it’s like searching for the right path in a fog. It takes time to find out which was the right one.

The third problem is that scientific uncertainty allows people to spin our results. We had a press conference for project I worked in called ice2sea, which made predictions of global average sea level rise using the physics-based methods. Some journalists reported our results as “Sea level rise to be less severe than feared” because they compared us with those higher, statistical studies. Other journalists reported the same press conference as “Risk from rising sea levels worse than feared”, because they chose to compare us to the previous report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change which, like us, used the physics methods, but didn’t tally every possible part of sea level rise. One website chose to go with “The End of London as we know it…”.

It’s no wonder the public are confused. Every media outlet tells the story it wants to tell.

But we as scientists haven’t always helped. We haven’t always sold the idea of uncertainty as not only inevitable but even exciting, and we’ve sometimes over-simplified our communication. That pause in warming of the atmosphere surprised the media and public, even though scientists always expected this kind of thing could happen in the short term. That’s because we focused too much on talking about the long-term average predictions, which smooth out the year-to-year changes.

We’ve also done a bad job at being available. How many climate scientists can you name? Where do you get your climate science from: interviews with scientists? More likely the media, politicians, and activists, whether environmental or sceptical. We’ve mostly kept our head below the parapet, for fear of attracting fire in communicating complex science in a politicised atmosphere. There are certainly days I hide away. But we need to be braver.

Things are changing. There are more of us online than ever, giving interviews and talks, and trying to explain the nuances of the science.

But we can do better. My colleagues Ed Hawkins, Doug McNeall and I wrote a journal article about the slowdown in atmospheric warming called “Pause for thought”, which we’re proud to say was the first journal article to use Twitter handles for the author contact information. We called on our colleagues to join us online and in the media, because the more that do, the easier it gets: the less we have to speak outside our comfort zone, and the more we can support each other.

I’d especially love more female scientists to get out there. In our society, men are often rewarded for being competitive. I like to think if there were more women involved, it might help naturally move things from a climate debate to a climate conversation.

And for that conversation I’d like to invite you, to the public, to come and find us. There are now hundreds of climate scientists on Twitter, and the small number of us that blog is growing. But we’re mostly engaging with those who are already passionate, the environmentalists and dissenters. We’d like to talk to more in the middle ground: the fence-sitters, the understandably confused.

So I’m curating a Twitter list of climate scientists: a directory of active researchers – physical scientists, computer scientists and statisticians – who are studying climate change and its impacts. You can find it from my Twitter profile, flimsin.

So far I’ve added 250 climate scientists. If you’re a climate scientist, or know one, tweet me to add to the list. And if you’d like to ask a climate scientist a question – to discuss a news article, or explain their results – then just read through the biographies and find some scientists to ask.

I hope this list will grow, and start conversations that help us deal better with uncertainty in climate science – perhaps even with the messy business of science itself. So if you’re confused about climate … puzzled about the pause … surprised about sea level … or just uncertain about uncertainty … please come and find us. We’d love to talk.

With enormous thanks to TED coach Michael Weitz and Head of TEDxCERN Claudia Marcelloni De Oliveira for helping me make this talk more accessible and clear. Thanks to Vice News for suggestions to improve the readability of my article, and to Jonty Rougier, Ed Hawkins and Doug McNeall for useful comments and encouragement.

You don’t have a science!

Look here:

http://s6.postimg.org/jb6qe15rl/Marcott_2013_Eye_Candy.jpg

“That’s what peer review corruption looks like!” – Occupy Climate Street

[ N.B. this refers to a conversation we started under the Vice News piece. My blog moderation policy doesn’t allow accusations like “corruption” (in either direction) – repeat offenders get snipped (by me). By the way, what did you think of my comment under the Vice piece about the important difference between sea ice and land ice? — Tamsin ].

Nicely done. Thank you. I like your take on climate as probability. I’ve never been comfortable with the notion of average weather. For one thing it doesn’t capture the idea that a range of weathers is by normal

I rid to go to your Twitter list, but was told the page doesn’t exist

Absolutely, the “average weather” is a simplification that can be a good start for some audiences but doesn’t describe the full probability distribution.

Think the link works? Though some tweeted versions didn’t. Let me know, as maybe it’s because I’m signed in to Twitter or something.

Sorry for delayed moderation by the way…

Tamsin said:

We’re confident the world will get warmer, shifting the hottest and coldest days further, and that rainfall will become heavier in some places, such as the wet tropical regions. Global average sea level will continue rising, making the extreme highs in sea level higher and more frequent.

For some reason when I read the above remarks a saying of the American humorist Will Rogers sprang to mind.

It’s not ignorance that hurts us, it’s the things we know that ain’t so.

The world stopped getting warmer 18 years ago. Doesn’t that dent your confidence?

Quote ‘We’re confident the world will get warmer, shifting the hottest and coldest days further, and that rainfall will become heavier in some places, such as the wet tropical regions. Global average sea level will continue rising, making the extreme highs in sea level higher and more frequent.’

That statement is hardly awe inspiring when you consider the £Bn’s spent on Climate research in the last 30 years.

After all that money being spent your confidences are no different (rainfall excepted ) from those someone who considers the data supports the warming in the last century was caused by a natural recovery from the LIA with little or no contribution from increased CO2 levels. The only difference (rainfall excepted ) is at some unknown point a new LIA will appear and temps and sea levels will drop until the next recovery.

Not good value for money whatever the side of the fence (or on top of it 😉 ) you sit. I would be embarrassed to be involved.

“But it’s not only climate scientists that are certain [the earth is warming]. Not everyone knows this, but more and more climate sceptics agree with us too.”

You’ve neatly side-stepped that sceptics were correct to question the “consensus” 0.2 deg. per decade forecast due to carbon-dioxide emissions. Although I do remember the Chairman of the IPCC admitting some time ago that natural warming had been dismissed as less important that it turns out to be.

I wish the remaining climatologists would admit that the ‘pause’ was an unexpected surprise and the forecast was for surface temperatures, not at the bottom of the sea (which latest papers indicate is unlikely, anyway).

There needs to be more admission from members of the ‘consensus’ that the research community was over-obsessed with carbon-dioxide as THE “driver” of warming – that it has a worse correlation with climate change than sunspots and ocean circulation. And also, that so little is known about the causes of cloud formation, that the atmosphere itself may create new clouds as co2 proportins increase. Has anybody looked?

Everybody is preoccupied by the climate change, but it is useless to discuss only the future whithout understanding the main cause of the climate transformation. My opinion is that the ocean and human activity on the ocean (mostly naval wars) has a big contribution in the matter. Aren’t we ignoring that? Shouldn’t we pay more attention to the ocean? For example, as you can see here, http://www.ocean-climate.com/, the two World Wars led to climate change.

https://ipccreport.wordpress.com/2014/09/26/tamsins-topsy-turvy-ted-talk/

Your thoughts?

(sigh) No, *the world* did not stop getting warmer 18 years ago.

Nice post.

I´d like to contribute a short story you may find interesting:

In the early 1990´s I worked on an Arctic project, which led me to build a dynamic system model. The model was intended to provide us ship navigation statistics. To put it simply, a ship will transit more efficiently if it has optimized horspower, add ons such as bow thrusters, the right hull shape, and sails in thinner or no ice. Arctic navigation is heavily influenced by sea ice, so we gathered as much data as we could get. This was supplemented with data from our own expeditions.

The information I saw told me the ice conditions were improving, and this was caused by regional warming. We were focused on the Arctic for a specific issue, and the climate experts we had were only asked to give us what we needed for our models, so I didn´t think much about global warming as such. When I started hearing about global warming I thought the basic idea was fine because it matched what I had learned and the data I had seen. Eventually the project was killed after we concluded we were way too early and the Arctic wouldnt give us a reliable navigation pathway for about 40 to 50 years.

You may also find this interesting: The issue is complicated by the bow shape problem. Bows designed to break ice are lousy open water bows, and vice versa. This was solved by Kvaerner Masa yards by designing a ship which sails in both directions, using the stern to break ice at slow speed and the bow to sail at high speed when it hits open water, but even this design didn´t give us the transit ability we wanted.

Later, in 2006, I saw that Al Gore video, and I approached a highly educated friend who was working in renewables business development (our corporation had an interest in seeing if renewables were a viable large scale investment option). When I mentioned the Al Gore movie he laughed and told me Gore was inflating the problem, but he didn´t understand why.

When I asked him why he felt Gore was exaggerating, he said the global warming issue was a key to the renewables investments, because they couldn´t fly on their own. This meant the global warming scare had to drive governments to offer subsidies, and the subsidies wouldn´t be available unless there was a real concern over global warming.

He continued to explain that, as far as he could see, the global warming issue was real but the experts he was talking to told him it was a much slower pace problem than the media and politicians believed, with temperature rise being a stairstep process which could run one half to one third the rates being expressed by the IPCC. This point really discouraged my friend because he really wanted to focus his career on renewables in general (he used to spend lunches lecturing us about miscanthus).

So eventually he changed career tracks, because he felt the renewables move within the corporation was a dead end (he was right, they invested some money and have kept researching it, but it never really blossomed).

What else can I add? I think the problem has been badly mishandled by exaggerating it, which was clearly caused by the climate model communities lack of history maching techniques (my impression is the models just lack the proper history matches, and can´t be tuned because they use so much computing power the matching approach is just too cumbersome?).

The other issue I see is the low quality of the work done to prepare for the integration of renewables in the power generation systems. It seems to have been dictated by politicians who were adviced by chimpanzees and lobbied by corporate interests focused on renewables as a money making proposition, money they would make via the subsidies they could get. And this is why the whole problem landed in a swamp.

Now we are involved in politics up to our necks with special interests pulling in all sorts of directions, feeding misinformation, buying politicians, and so on. And it goes both ways. This is a big game in which everybody plays. And meanwhile, to complicate matters, we are running out of oil.

And who, pray tell Feranndo, was ‘he’ and who were ‘the experts he was talking to’ who ‘told him it was a much slower pace problem than the media and politicians believed, with temperature rise being a stairstep process which could run one half to one third the rates being expressed by the IPCC.’– back in 2006?

Anecdotes are anecdotes. Not science. It’s not enough that you’ve, gotten slapped around on RealClimate, Rabbett Run, etc for your obfuscations, have to start here too? Tamsin’s point is about uncertainty. Yet you are certain the ‘problem’ has been ‘exaggerated’.

Meanwhile, the uncertainty runs *both* ways.

Steven, I described for Tamsin what I have seen working in a corporate environment. This included a brief overview of what we were doing in the Arctic (focused on ship navigation and mooring issues), as well as my friend´s aborted career focus on renewables.

The post was about uncertainty. I faced the problem when trying to determine whether we would stick with our Arctic project, felt the outcome was way too uncertain, and suggested to our management we should end our efforts. Thus far it seems I was right (the ice isn´t disappearing at a predictable pace and navigation in the Arctic is a very dangerous proposition). My friend faced a similar uncertainty, which happened to be very real for him: Should he tie his career to renewables or should he go do something else? He felt the career move depended on the global warming pace, and whether it would induce government to offer lots of renewables subsidies. In the end, he too punted because he felt the warming pace wouldn´t be fast enough. He was right.

Finally, by now you should realize I´m not deterred by the bad manners some people exhibit in blogs. It would really help the contents if you try to use an improved vocabulary.

When will you lab coat consultants say your Human CO2 “THREAT TO PLANET” is now; “proven” or at least say your scientific method won’t “allow” you to?

How can history not declare climate change’s 32 years of needless panic; a pure war crime?

“The extra energy means the atmosphere and the surface of the ocean have warmed … As the oceans heat up they expand” … These already are contentious statements. There are scores of studies that seem to point out that by correcting for all other possible factors sea level has not risen by any significant amount that could be attributed to warming. And these problems between science and society (which is often is interpreted as if “socitey doesn’t get it” and “if they don’t get it, but are intelligent, they must be lobbyists”) are actually created by certain “reputable” climate science institutions hiding data from FOIA requests or ignoring evidence of heat insulae effects of existing temperature gauges which over the years have been warmed not by “trapped solar heat” but by buildings erected around them and by air craft fumes not present when they were installed. No amount of how difficult the planet’s systems are as against the particle “zoo” (actually the latter is more complex than the variables climate science currently tracks …) will convince a scientist outside these circles which has lead one of your profession, the eminent Nobel prize winner who researched super-conductivity to give talks about climate science having become a “religion”.

You had the chance, at the slr portion, to point out that slr has not significantly changed in many decades. You seem to have punted. That is too bad.

Noticed your post at Wattsupwiththat, searched for Dr Edwards and found you at Bristol Uni and this blog.

Here you writes:

“I used to be a particle physicist. Sadly, I left before it became cool to be a particle physicist.”

“Now that I’m a climate scientist”

What will you do when it’s no longer cool to be a climate scientist?

I suggest nuclear engineering. (The sooner the better) There is need for professionals like you, to bring electricity to the poor in SS Sahara.

It starts with 6 new plants in South Africa.

How large are the uncertainties in measuring the earth’s energy budget?

Nicely done! I’m a newly retired electrical engineer so I’ve had enough physics to know I don’t know enough yet. Fascinated by the pause in warming but continued loss of arctic ice. I’ll be reading papers and following the blog. It would be nice if all the science journals would suspend charging for any papers related to climate change, since it is an issue that affects us all. (Might be a gesture that would make the news and gain public support). Thanks!

Defining “climate”, particularly “global climate”, in terms that are useful for a political response to what we are currently seeing happening in our weather isn’t straightforward. I’d be interested in any literature that addresses the measurement problem.

The problem as I see it is that at the level of the globe there are only a small number of attributes that can reliably measured even in the relatively modern history. The way we define “climate” really means we have data for only half a dozen different periods of climates over the last 200 years at the best, and for those we can probably only estimate global temperatures and precipitation, with some ability to give crude geographical subdivisions. Across these half dozen data points we are probably seeing transitions as well as steady states, so the amount of available historic data diminishes accordingly.

From this we are then expected to forecast/project future climates a century out and in those forecasts incorporate variables that might be subject to human intervention and to quantify their impact. The process being used to do this is to attempt to model the weather and from that to identify patterns that represent different climates and attribute causality within those models.

I frankly think that the modellers are on a hiding to nothing in this game. Because they have very limited historic data their estimates of what separates weather (aka natural variability) from climate is going to be extremely unreliable or arbitrary. Was the global weather that was experienced 1800-29 sufficiently different from that experienced from (say) 1960-1989 to warrant calling it a different climate? Do the weather measurement errors even let us tell the difference, let alone argue the weather distributions were sufficiently different to put a dividing line in.

In practice I suspect even if you look over the last couple of millennia you might be able to argue for perhaps three global climate states (little ice age, MWP and ‘tweens), and it would seem appropriate to start with some simple operational definition of these (or some similar classification). One suspects that for any policy purpose global temps would be adequate to define the climate, and going beyond this would be stretching the quality of the data we have. An important characteristic of the policy problem is that the response can be heuristic as better information becomes available.

In this light the policy question becomes: are we likely to see the climate move to the state beyond the MWP by (say) 2050-79? If the answer is “yes” we then want to know what the risks are and what can we do about it (mitigation/avoidance). If we answer “we can’t tell” then we also need to know what we should keep an eye on and on what timescale might greater certainty evolve? I should add that the risks need to be objectively assessed – the practice of erring on the safe side in the name of precaution completely stuffs things up for any sensible policy response.

I’m doubtful of the utility of using climate models to produce weather runs to forecast future climate states for this purpose. The problem is much simpler and cruder than that and the climate models give a false sense of precision. They may however be useful to investigate change and transition points in the climate history.

So to summarise, we lack the information to support sophisticated characterisations of the climate and the policy maker doesn’t really need them for their purposes. If we look at the way we could deal with the policy maker’s problem we’d be unlikely to start with the climate models we’re currently using. The level of detail being investigated is distracting from the much more important policy problem of how to best manage the uncertainty.

This is not so much an issue for the modelers, it calls for better definition of the policy needs. Hopefully this will emerge from the current weather patterns not conforming to the simple prescriptions of the models, and this will bring about a better understanding by the policy wonks of uncertainty in this game and how it hasn’t been licked and how to deal with that.

“When I asked him why he felt Gore was exaggerating, he said the global warming issue was a key to the renewables investments, because they couldn´t fly on their own. This meant the global warming scare had to drive governments to offer subsidies, and the subsidies wouldn´t be available unless there was a real concern over global warming.”

It’s interesting that you don’t notice what is wrong with this. He didn’t tell you why he thought Gore was exaggerating, he gave you a possible explanation for why Gore might have exaggerated if it were established that he had.

And yet, you go on to talk about exaggeration as if it were an established fact. But it’s not; it’s just a science-rejector talking point, arrived at through such fallacious and intellectually dishonest processes as the above. The facts about Al Gore and his movie is that it was a quite accurate reflection of the understanding of climate scientists at the time … far more accurate than almost any other movie on any topic. Of course, science rejectors have gone on to misrepresent Gore and his movie, as you have done here.

Standard issue false claims by a science rejector.

We know that main cause of the climate transformation, and it’s not that. You should pay more attention to the science and less to your own baseless opinion.

“The world stopped getting warmer 18 years ago. ”

No, it didn’t.

” Doesn’t that dent your confidence?”

Apparently the information in this very article you’re responding to doesn’t dent yours.

“that it has a worse correlation with climate change than sunspots and ocean circulation”

This is nonsense that has been repeatedly debunked.

Debunking data is usually on-line and linked — links are almost as cheap as hot air, but usually give more authority than just the words.

Any question that needs to be repeatedly debunked implies that earlier debunking, for some reason, was not so convincing. Calling a skeptic’s debatable claim nonsense is excellent for making such a skeptic certain that your side is at least rude, and most on-the-fence observers pretty sympathetic to skeptics — none of whom got a Nobel for any “inconvenient truths”, altho “global warming” has been so unproven by measured temperatures that the alarmists have even given up that name.

“Any question that needs to be repeatedly debunked implies that earlier debunking, for some reason, was not so convincing. ”

That, like everything we see from the science rejectors, is grossly intellectually dishonest. Science rejector talking points get repeatedly debunked because the numerous science rejectors bring up the same talking points over and over again because a) they are ideologues, b) they are not well informed, and c) they simply ignore the rebuttals.

“a skeptic”

They aren’t skeptics, they are gullible ideologues who believe anything and everything that hints at being contrary to AGW, even when inconsistent with each other.

” “global warming” has been so unproven by measured temperatures that the alarmists have even given up that name”

Yet another blatant lie from a science rejector.

As for term “alarmist”, which is typical of the hypocrisy of science rejectors who whine about people being “rude” by calling out their lies: even the most conservative cautious and shy climate scientists are now sounding the klarion.

Thanks for a great post, haven’t been here in a while since there hasn’t been so many posts. Glad you’ll be on Open University, hope you can have “trailers” here that point at your course (which I don’t have time to take).

I made a reply to Marcel Kincaid, who made a couple of replies to some “on the fence” folk (which you say you want more of) that are basically — you’re wrong, your “fact” is nonsense. But no links.

It would be too hard to be a very active comment arbitrator, but you might have more discussion if those who had facts or counter facts would be encouraged to link to and restate (briefly) the facts.

Where is the best set of historical temp data that could be used to say what the trends have been in the measured City/ Farm temperatures over the last 200, 1000 years? I’m sure London, Paris, Berlin, Rome, Madrid have long histories. Boston & New York a few hundred, too. I suspect they show not much warming for the last 18 years.

Finally, the issue of gov’t action, and subsidies for boondoggles like Solyndra should be more explicit in the debate — if “thinking there is a problem” means support for gov’t waste and cronyism, lots of folk will accept “problem’s not that big” rather than support silly waste just to “do something”.

“I suspect they show not much warming for the last 18 years.”

Of course you do. This isn’t skepticism, it’s ideology.

Meanwhile, it has gotten hotter and hotter in the 7 years since that was written.